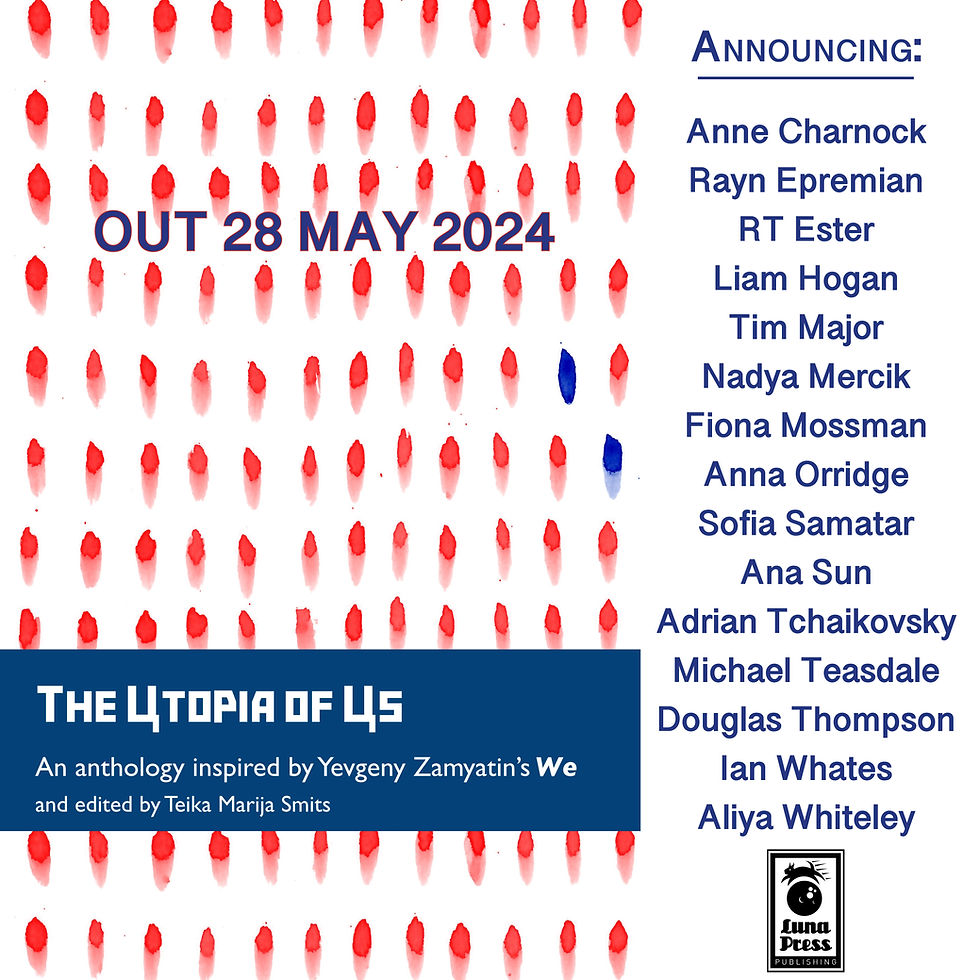

The Utopia of Us anthology is now available for pre-order! Editor Teika Marija Smits has brought together 15 incredible writers and their stories, directly inspired by We by Yevgeny Zamyatin.

It is a charity anthology, and given Russia's current war with Ukraine, royalties from the book will be donated to the Ukraine Humanitarian Appeal.

If you pre-order directly from the Luna website, you will also receive a discount. Check it out!

Today we'd like to introduce you to Michael Teasdale and the story "Art-crime – Artifacts – Age of Birds".

About the author:

MICHAEL TEASDALE is an English author and member of the SFWA. His work can be found in anthologies by Air and Nothingness Press, Tyche Books and World Weaver Press. His stories have also appeared in the pages of Shoreline of Infinity and Wyldblood Magazine with audio adaptations of his work appearing via Havok Story Podcast and The Other Stories. He lives in Transylvania, Romania with his partner and three cats and can be followed on social media @MTeasdalewriter

Michael on the story:

I can trace my relationship with Zamyatin and We back to the turn of the millennium when I began to make my first tentative steps into online shopping (back in the days when Amazon seemed like a quirky indie project!). At this point I’d been on a run of reading, and in some cases re-reading, the dystopias (both imagined and real) of Huxley, Koestler and Orwell and all sources pointed to Zamyatin’s work as being an unexplored foundation on which the latter built the Ministry of Truth.

Back then, I lived in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, a place I was surprised to learn that Zamyatin himself had lived and worked for a spell. There he constructed icebreakers in the Swan Hunter shipyards of Wallsend, just a short distance from the places I would pass, my nose buried in his novel, on my daily commute.

While life has since pulled me all around the world, I have thought about We and its haunting imagery many times in the decades that followed. Yet, beyond the Integral, the glass houses and the city of straight lines, it is a particular comment in the book’s intended preface that still resonates. Here Zamyatin reveals how “I wrote for those who can not only walk, not only march in time, but fly as well.”

These last few years have filled me with dread for the future of art and literature. It is not the rise of AI itself that has been terrifying to watch, but just how badly I feel we have gotten it wrong and just how worryingly we are embracing its dehumanising and dystopic elements over the solutions it should have presented. This technology, which was supposed to liberate us from drudgery and free up time for creativity, now threatens to clip our wings and usurp us in the manner of the novel-writing machines of 1984.

The story I wrote for this anthology is a reflection of my fears. A place where this timeline could end in a world touched by the mad-logic of the Integral’s message. Yet it is also the story of the hope that burns among those of us unwilling to abandon human imagination to the quick and easy convenience of the machine.

I chose the symbol of the bird as the cornerstone of the uprising taking place in my story as a reflection of We’s own avian repopulation but also to mirror Zamyatin’s message on why we write. As artists and as lovers of the arts, I believe we must not only fly but also bear our talons (or our pencils) against a future that does not have to be as inevitable as we are told.

As Zamyatin said, “There will always be uprisings, revolutions, they are necessary – like storms – so that the sun should become more dazzling.”

I’m certain we must prevail, because art must prevail.

More on the anthology:

The year 2024 marks the centenary of the first publication of We, the direct inspiration for George Orwell’s 1984, and many other novels, such as Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed and Kurt Vonnegut’s Player Piano.

Strikingly, the Russian novel was first published in English, and in the US. Indeed, it wasn’t until 1988 that it was published in the author’s native country. Clearly, this was a book that the people in power in the Soviet Union wanted erased. Yet it ushered in a new genre – the future dystopia – and in doing so gave birth to the many dystopian novels and films which have found their way into our popular culture.

Setting aside what its publication history says about Russia’s past, it also happens to be a beautifully written and page-turning novel, and one that is still currently relevant since it speaks to the very heart of what it means to be human. In short, the centenary of this wonderful novel should be, and needs to be, celebrated, and how better to do that than by a globally minded, independent press, publishing an anthology of science fiction stories inspired by We?

Commentaires